The Association for Middle East Women’s Studies (AMEWS) Book Award recognizes and promotes excellence in the field of Middle East gender, women’s and sexuality studies. The award is offered annually to a scholar for a solo-authored book. Books published (copyrighted) in 2023 will be considered for the 2024 award. The competition is open only to books published in English. The winner is recognized at the annual meeting of the Middle East Studies Association and receives a monetary prize. Other books deemed exceptional may receive an honorable mention.

AMEWS Book Award Committee:

- Ellen McLarney

- Amy Kallander

- Hatoon Alfassi

For more information previous winners see below.

Books must be nominated from one or more individuals using the AMEWS Book Award Nomination Form 2024 to attest to the quality and potential impact of the particular work on the field of Middle East gender, sexuality, feminist, and women’s studies. Self-nomination is permitted. Copies of the nominated book must also be sent to the individual Award Committee members (3 in total) listed below under “Instructions.” Works submitted without an accompanying nomination form and book copies will not be considered–both are required.

The deadline to submit the nomination form and the three copies of each nominated book is June 17, 2024. If you have any questions about the book award process, please contact Ellen McLarney at ellenmc@duke.edu with any questions.

Requirements:

- Books published between January 1, 2023 and December 31, 2023 are eligible for this year’s award.

- Books should be solo authored.

- Books must be non-fiction scholarly monographs based on original research. Works that are not eligible include edited collections and compilations, proceedings of symposia, new editions of previously published books, bibliographies, dictionaries, textbooks, and surveys.

- Books that have already been nominated for this book award cannot be renominated.

To Nominate a Book:

- The deadline is June 17, 2024

- Authors or nominators should fill out https://forms.gle/MJVo54rJEVEW3whKA.

- Send copies of the book to each of the three members of the committee (information below).

- The books should be postmarked by June 1, 2024, addresses can be found below.

Instructions:

Submit nomination form via https://forms.gle/MJVo54rJEVEW3whKA by June 17, 2024.

Mail one copy of the nominated book to the members of the Book Award Committee:

Ellen McLarney

3901 Darby Road

Durham, NC 27707

Amy Kallander

145 Eggers Hall

Syracuse University Syracuse, NY 13244

Hatoon Alfassi

P.O. Box 6710

Riyadh 11452, Saudi Arabia

hatoon.alfassi@manchester.ac.uk

The nomination is not complete until each member of the committee receives a copy of the nominated book, which should be postmarked by June 1, 2024 to ensure delivery by June 17, 2024. Books cannot be returned.

2023 Prize Winner

Maya Mikdashi (Rutgers University): Sextarianism: Sovereignty, Secularism, and the State in Lebanon (Stanford University Press, 2022)

This thoughtful ethnography of religion, conversion, the judicial system, marriage, and family in Lebanon offers a poignant theoretical intervention in both Middle East Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. The book examines how “sex, sexuality, and sect structure legal bureaucratic systems” in terms of ideology and law, and how state power manages sexual differences in ways that are new (2).

Sextarianism is a poignant ethnographic study of state power, illustrating how “[sectarian citizens] are structurally produced through laws and bureaucracies that regulate sexuality and gender” in (post)colonial Lebanon (28). This interdisciplinary project cuts across the fields of political anthropology, gender studies, legal studies, and religious studies, offering nuanced evidence-based insights that are epistemologically, theoretically, and methodologically convincing and creative. It is deeply reflective and undeniably rigorous. Equally important, the project in its entirety pays careful attention to the ethics, poetics, and politics of knowledge production. It disrupts established knowledge hierarchies and neatly compartmentalized binaries of here and there, of now and then, of self and other. It’s not merely about the disparate archives Mikdashi assembles or the margins she re-centers or the narratives that she weaves so beautifully into her thick analyses of sex-sexuality-sect. It is also about the embodied writing practice, the ways in which the author explicitly identifies and theorizes her entanglements in the project. How she writes, who she writes, and what bodies of scholarship she draws on. All of this together makes Sextarianism an award-winning book.

2022 Prize Winners

Amidst ongoing wars and insecurities, female fighters, politicians and activists of the Kurdish Freedom Movement are building a new political system that centres gender equality. Since the Rojava Revolution, the international focus has been especially on female fighters, a gaze that has often been essentialising and objectifying, brushing over a much more complex history of violence and resistance. Going beyond Orientalist tropes of the female freedom fighter, and the movement’s own narrative of the ‘free woman’, Isabel Käser looks at personal trajectories and everyday processes of becoming a militant in this movement. Based on in-depth ethnographic research in Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan, with women politicians, martyr mothers and female fighters, she looks at how norms around gender and sexuality have been rewritten and how new meanings and practices have been assigned to women in the quest for Kurdish self-determination. Her book complicates prevailing notions of gender and war and creates a more nuanced understanding of the everyday embodied epistemologies of violence, conflict and resistance.

Sovereign Attachments rethinks sovereignty by moving it out of the exclusive domain of geopolitics and legality and into cultural, religious, and gender studies. Through a close reading of a stunning array of cultural texts produced by the Pakistani state and the Pakistan-based Taliban, Shenila Khoja-Moolji theorizes sovereignty as an ongoing attachment that is negotiated in public culture. Both the state and the Taliban recruit publics into relationships of trust, protection, and fraternity by summoning models of Islamic masculinity, mobilizing kinship metaphors, and marshalling affect. In particular, masculinity and Muslimness emerge as salient performances through which sovereign attachments are harnessed. The book shifts the discussion of sovereignty away from questions about absolute dominance to ones about shared repertoires, entanglements, and co-constitution.

Honorable Mention

The Taliban made piety a business of the state, and thereby intervened in the daily lives and social interactions of Afghan women. Pious Peripheries examines women’s resistance through groundbreaking fieldwork at a women’s shelter in Kabul, home to runaway wives, daughters, mothers, and sisters of the Taliban. Whether running to seek marriage or divorce, enduring or escaping abuse, or even accused of singing sexually explicit songs in public, “promiscuous” women challenge the status quo—and once marked as promiscuous, women have few resources. This book provides a window into the everyday struggles of Afghan women as they develop new ways to challenge historical patriarchal practices.

Sonia Ahsan-Tirmizi explores how women negotiate gendered power mechanisms, notably those of Islam and Pashtunwali. Sometimes defined as an honor code, Pashtunwali is a discursive and material practice that women embody through praying, fasting, oral and written poetry, and participation in rituals of hospitality and refuge. In taking ownership of Pashtunwali and Islamic knowledge, in both textual and oral forms, women create a new supportive community, finding friendship and solidarity in the margins of Afghan society. So doing, these women redefine the meanings of equality, honor, piety, and promiscuity in Afghanistan.

2021 Prize Winner

Celene Ibrahim

Women and Gender in the Qur’an (Oxford University Press, 2020)

This well-written book presents a range of different female major and minor female figures in the Qur’an, trying to situate them along an arc of sacred history. Stressing the non-linearity of narratives and the primary concern with the genesis and fate of human beings, the author presents the progression of female characters, while examining different narratives. Ibrahim’s work centers women in the Qur’an and works to expand our understanding of gender and sexuality in Islam, innovative in field of Qur’anic and Islamic studies. She explores representations of reproduction, kinship, sexed bodies, and female embodiment. Ibrahim offers thought-provoking analysis about women and gender in the Qur’an, contributing to growing and important scholarship.

2020 Prize Winner

Judith Surkis, Sex, Law, and Sovereignty in French Algeria, 1830-1930 (Cornell University Press 2019)

The book is an excellent and incredibly well-researched account of the French occupation’s sexualization of Algerians as an imperial tool of control. Judith Surkis unearths the colonial archive of French Algeria and shows how the focus on Muslim personal status law and its sexualization of men and women enabled the legal and political racial distinctions between the Algerian and French populations; thus making the entire colonial project discursively and physically possible. The author brilliantly makes a case for the power of law as a tool of racial governmentality, and shows how Algerians, women and men, attempted to resist the power of the law as a tool as imperial control. The author’s analysis of case law, French jurisprudence, legal opinions, and journalistic articles make for a powerful new gendered reading of the French imperialist project in Algeria, and how sexual and racial differences, as well as gun power, made it possible.

The author tells a very compelling and engaging story while also making a nuanced and sophisticated argument about the centrality of law in the context of Algeria’s colonization by France. Gender, that is constructions of normative Algerian femininity and masculinity as well as gender relations, including ideas about sexuality and the family were key in constructing differences between the Algerian subjects and French citizens. To be more precise: French male citizens as well as French women were simultaneously fighting for their political rights and full citizenship, often using the language and logic of imperialist feminism to do so. A very original angle is the discussion of how French interpretation and construction of “Muslim family law” not only worked towards their land and properly appropriation but also confused questions of property and family, government and religion.

This study is an outstanding example of what happens when a feminist humanist undertakes scholarship on jurisprudence and case law. Accessible, thoroughly researched and presented so that all the complexities of the events, political decisions, court judgments and social implications are clear.

2020 Honorable Mention

Sara Pursley, Familiar Futures: Time, Selfhood, and Sovereignty in Iraq (Stanford University Press 2019)

Iraq was the first postcolonial state recognized as legally sovereign by the League of Nations amid the twentieth-century wave of decolonization movements. It also emerged as an early laboratory of development projects designed by Iraqi intellectuals, British colonial officials, American modernization theorists, and postwar international agencies. Familiar Futures considers how such projects—from the country’s creation under British mandate rule in 1920 through the 1958 revolution to the first Ba’th coup in 1963—reshaped Iraqi everyday habits, desires, and familial relations in the name of a developed future.

Sara Pursley investigates how Western and Iraqi policymakers promoted changes in schooling, land ownership, and family law to better differentiate Iraq’s citizens by class, sex, and age. Peasants were resettled on isolated family farms; rural boys received education limited to training in agricultural skills; girls were required to take home economics courses; and adolescents were educated on the formation of proper families. Future-oriented discourses about the importance of sexual difference to Iraq’s modernization worked paradoxically, deferring demands for political change in the present and reproducing existing capitalist relations. Ultimately, the book shows how certain goods—most obviously, democratic ideals—were repeatedly sacrificed in the name of the nation’s economic development in an ever-receding future.

2020 Honorable Mention

Sherine Hafez, Women of the Midan: The Untold Stories of Egypt’s Revolutionaries (Indiana University Press 2019)

In Women of the Midan, Sherine Hafez demonstrates how women were a central part of revolutionary process of the Arab Spring. Women not only protested in the streets of Cairo, they demanded democracy, social justice, and renegotiation of a variety of sociocultural structures that repressed and disciplined them. Women’s resistance to state control, Islamism, neoliberal market changes, the military establishment, and patriarchal systems forged new paths of dissent and transformation. Through firsthand accounts of women who participated in the revolution, Hafez illustrates how the gendered body signifies collective action and the revolutionary narrative. Using the concept of rememory, Hafez shows how the body is inseparably linked to the trauma of the revolutionary struggle. While delving into the complex weave of public space, government control, masculinity, and religious and cultural norms, Hafez sheds light on women’s relationship to the state in the Arab world today and how the state, in turn, shapes individuals and marks gendered bodies.

2020 Honorable Mention

Zahra Ayubi, Gendered Morality: Classical Islamic Ethics of the Self, Family, and Society (Columbia University Press, 2019)

Islamic scriptural sources offer potentially radical notions of equality. Yet medieval Islamic philosophers chose to establish a hierarchical, male-centered virtue ethics. In Gendered Morality, Zahra Ayubi rethinks the tradition of Islamic philosophical ethics from a feminist critical perspective. She calls for a philosophical turn in the study of gender in Islam based on resources for gender equality that are unlocked by feminist engagement with the Islamic ethical tradition.

Developing a lens for a feminist philosophy of Islam, Ayubi analyzes constructions of masculinity, femininity, and gender relations in classic works of philosophical ethics. In close readings of foundational texts by Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali, Nasir-ad Din Tusi, and Jalal ad-Din Davani, she interrogates how these thinkers conceive of the ethical human being as an elite male within a hierarchical cosmology built on the exclusion of women and nonelites. Yet in the course of prescribing ethical behavior, the ethicists speak of complex gendered and human relations that contradict their hierarchies. Their metaphysical premises about the nature of the divine, humanity, and moral responsibility indicate a potential egalitarian core. Gendered Morality offers a vital and disruptive new perspective on patriarchal Islamic ethics and metaphysics, showing the ways in which the philosophical tradition can support the aims of gender justice and human flourishing.

2019 Prize Winner

Hila Amit, A Queer Way Out: The Politics of Queer Emigration from Israel (SUNY Press 2018)

The very language of Zionism prizes the concept of immigration to Israel (aliyah, literally ascending) while stigmatizing emigration from Israel (yerida, descending). In A Queer Way Out, Hila Amit explores the as-yet-untold story of queer Israeli emigrants. Drawing on extensive fieldwork in Berlin, London, and New York, she examines motivations for departure and feelings of unbelonging to the Israeli national collective. Amit shows that sexual orientation and left-wing political affiliation play significant roles in decisions to leave. Queer Israeli emigrants question national and heterosexual norms such as army service, monogamy, and reproduction. Amit argues that emigration itself is not only a political act, but one that pioneers a deliberately unheroic form of resistance to Zionist ideology. This fascinating study enriches our understandings of migration, political activism, and queer forms of living in Israel and beyond.

The very language of Zionism prizes the concept of immigration to Israel (aliyah, literally ascending) while stigmatizing emigration from Israel (yerida, descending). In A Queer Way Out, Hila Amit explores the as-yet-untold story of queer Israeli emigrants. Drawing on extensive fieldwork in Berlin, London, and New York, she examines motivations for departure and feelings of unbelonging to the Israeli national collective. Amit shows that sexual orientation and left-wing political affiliation play significant roles in decisions to leave. Queer Israeli emigrants question national and heterosexual norms such as army service, monogamy, and reproduction. Amit argues that emigration itself is not only a political act, but one that pioneers a deliberately unheroic form of resistance to Zionist ideology. This fascinating study enriches our understandings of migration, political activism, and queer forms of living in Israel and beyond.

2019 Honorable Mention

Wim Peumans, Queer Muslims in Europe: Sexuality, Religion, and Migration in Belgium (I.B. Tauris 2018)

Belgium was the second country in the world to introduce same-sex marriage. It has an elaborate legal system for protecting the rights of LGBT individuals in general and LGBT asylum seekers in particular. At the same time, since 2015 the country has become known as the `jihadi centre of Europe’ and criticized for its `homonationalism’ where some queer subjects – such as ethnic, racial and religious minorities, or those with a migrant background – are excluded from the dominant discourse on LGBT rights.

Queer Muslims living in the country exist in this complex context and their identities are often disregarded as implausible. This book foregrounds the lived experiences of queer Muslims who migrated to Belgium because of their sexuality and queer Muslims who are the children of economic migrants. Based on extensive fieldwork, Wim Peumans examines how these Muslims negotiate silence and disclosure around their sexuality and understand their religious beliefs. He also explores how the sexual identity of queer Muslims changes within a context of transnational migration. In focusing on people with different migration histories and ethnic backgrounds, this book challenges the heteronormativity of Migration Studies and reveals the interrelated issues involved in migration, sexuality and religion. The research will be valuable for those working on immigration, refugees, LGBT issues, public policy and contemporary Muslim studies.

2018 Prize WinnerAttiya Ahmad, Everyday Conversions: Islam, Domestic Work, and South Asian Migrant Women in Kuwait (Duke University Press, 2017).

This excellent book is the product of several years Attiya Ahmad spent in Kuwait and some time in Nepal. From the beginning Ahmad inserts herself as a transnational Canadian-Pakistani feminist Muslim into this keenly observed, and deeply textured ethnography of South Asian women, some of them have lived in Kuwait for up to 40 years. She explores the question: Why are domestic workers converting to Islam in the Arabian Gulf region? In Everyday ConversionsAhmad presents us with an original analysis of this phenomenon.

This excellent book is the product of several years Attiya Ahmad spent in Kuwait and some time in Nepal. From the beginning Ahmad inserts herself as a transnational Canadian-Pakistani feminist Muslim into this keenly observed, and deeply textured ethnography of South Asian women, some of them have lived in Kuwait for up to 40 years. She explores the question: Why are domestic workers converting to Islam in the Arabian Gulf region? In Everyday ConversionsAhmad presents us with an original analysis of this phenomenon.

The book begins and ends with Islamic centers: first, Al-Huda a Pakistani Urdu-speaking women’s movement; finally, Kuwait’s Islamic Da’wa Women’s Center for international non-Muslims and Muslims wanting to deepen their faith. Ahmad analyzes women’s transnational suspension between Kuwaiti and South Asian homes. Each chapter begins with a vignette that is then elaborated through “storytelling” that consists of recorded conversations and intricate observations that draw the reader into an almost novelistic account of the lives of her 24 subjects.

The definition of “everyday conversions” emerges gradually throughout the book so that we understand conversion not as a strictly religious phenomenon but as a total and very gradual change that ultimately motivates a religious decision as the culmination of everyday conversions. Ahmad contests the usual reasons given for migrants’ conversions and unrolls the patterns of their daily lives to show that conversion is not a sudden response to coercion or a desire for better treatment but a slow acceptance of fitraand Islam’s accommodation of previous religious identities by naramwomen.

One of the book’s key words is naram, a term applied to South Asian women. Naram, far from unskilled labor, “requires the development of skills, language abilities, and sets of cross-cultural and religious knowledge, but also necessitates the cultivation of dispositions and ongoing self-disciplining with respect to interpersonal interactions.” It entails emotional labor to fit into specific households: “being naramis like glue for women’s families… it resonates with the fluid, flexible student-centered pedagogies of Kuwait’s Islamic da’wa movement, thus facilitating domestic workers’ learning of Islamic precepts and practices.” Kuwait’s Da’wa movement develops “a contingent form of cosmopolitanism based on resonance, not synthesis or dialectic” and does not supersede previous identities.

Ahmad considers the household central to the production of ethno-national and transnational belongings and subjectivities. The temporariness of their jobs and their personal suspension between two homes should not to be resolved into diasporic identity that indicates discomfort. “Dual agents of reproduction,” they are considered “essential to the everyday functioning” of both households. From remittances to South Asia to immersion in their Kuwaiti families, from birth to death, produces real affection. Ahmad’s analysis of the kafala system and changing relationships between Kuwaitis and growing numbers of migrant workers highlights the importance of gender with men segregated in dormitories and poor accommodations (where she stayed) and women being part of every aspect of Kuwaitis’ lives.

In examining the connections between migration, labor, gender, and Islam, Ahmad complicates conventional understandings of the dynamics of religious conversion and the feminization of transnational labor migration. She proposes the concept of everyday conversion as a way to think more broadly about emergent forms of subjectivity, affinity, and belonging.

For book cover description, visit publisher site.

2018 Honorable Mention

Mehammed Amadeus Mack, Sexagon: Muslims, France and the Sexualization of National Culture (Fordham University Press, 2017).

Building on France’s moniker as the hexagon, Mehammed Amadeus Mack’s Sexagoncritically examines the way the figure of the young, virile, hypermasculine Muslim from the banlieuesof Paris serves as a counterpoint to liberal French secular society’s understanding of gender and sexuality. Surveying a wide range of representations of young Muslim men and women in the banlieuesof Paris, Mack demonstrates how North African immigrant and diasporic communities in France are shaped through postmulticultural discourses of inclusion and exclusion that depend on sexualized assumptions about these communities.

Building on France’s moniker as the hexagon, Mehammed Amadeus Mack’s Sexagoncritically examines the way the figure of the young, virile, hypermasculine Muslim from the banlieuesof Paris serves as a counterpoint to liberal French secular society’s understanding of gender and sexuality. Surveying a wide range of representations of young Muslim men and women in the banlieuesof Paris, Mack demonstrates how North African immigrant and diasporic communities in France are shaped through postmulticultural discourses of inclusion and exclusion that depend on sexualized assumptions about these communities.

Mack’s book is a sophisticated study that provides deep analysis of wide range of sources and employs a cultural studies framework in a way that challenges canonical queer theories. In particular, Mack’s troubling of liberal-secularist “coming out” narratives through a critical interrogation of clandestinity opens up new ways of thinking about visibility in relation to queerness and queer communities in the Franco-Arab context. Theorizing sexual clandestinity as a site for unregulated possibilities, whether liberatory or not, Sexagoncan be aligned with cutting edge work in queer of color theory.

Using the analytic of “virility,” rather than masculinity, to explore elements of vigor, assertiveness, combativeness, and ambition in Franco-Arab men and women of the banlieues, Mack shows how Muslim youth work on and against narratives that cast them as both hypersexualized and subject to sexually intolerant cultures.

Taken together, the organizing concepts of clandestinity and virility demonstrate how Franco-Arab youth have found ways of subverting the official scrutiny of the French Republic and to thwart its desires for universalism and transparency. Clandestinity, in its impenetrability, at once baffles liberal-savior narratives of sexual liberation and homonormativity even as it creates more complex queerings of intersectional identities.

For book cover description, visit publisher site.

2017 Prize Winner

Hanan Hammad, Industrial Sexuality: Gender, Urbanization and Social Transformation (UT Austin Press 2016).

Millions of Egyptian men, women, and children first experienced industrial work, urban life, and the transition from peasant-based and handcraft cultures to factory organization and hierarchy in the years between the two world wars. Their struggles to live in new places, inhabit new customs, and establish and abide by new urban norms and moral and gender orders underlie the story of the making of modern urban life—a story that has not been previously told from the perspective of Egypt’s working class.

Millions of Egyptian men, women, and children first experienced industrial work, urban life, and the transition from peasant-based and handcraft cultures to factory organization and hierarchy in the years between the two world wars. Their struggles to live in new places, inhabit new customs, and establish and abide by new urban norms and moral and gender orders underlie the story of the making of modern urban life—a story that has not been previously told from the perspective of Egypt’s working class.

Reconstructing the ordinary urban experiences of workers in al-Mahalla al-Kubra, home of the largest and most successful Egyptian textile factory, Industrial Sexuality investigates how the industrial urbanization of Egypt transformed masculine and feminine identities, sexualities, and public morality. Basing her account on archival sources that no researcher has previously used, Hanan Hammad describes how coercive industrial organization and hierarchy concentrated thousands of men, women, and children at work and at home under the authority of unfamiliar men, thus intensifying sexual harassment, child molestation, prostitution, and public exposure of private heterosexual and homosexual relationships. By juxtaposing these social experiences of daily life with national modernist discourses, Hammad demonstrates that ordinary industrial workers, handloom weavers, street vendors, lower-class landladies, and prostitutes—no less than the middle and upper classes—played a key role in shaping the Egyptian experience of modernity.

2017 Honorable Mention

Madeline Otis Campbell, Interpreters of Occupation: Gender and the Politics of Belonging in an Iraqi Refugee Network (Syracuse University Press 2016).

During the Iraq War, thousands of young Baghdadis worked as interpreters for US troops, becoming the front line of the so-called War on Terror. Deployed by the military as linguistic as well as cultural interpreters—translating the “human terrain” of Iraq—members of this network urgently honed identification strategies amid suspicion from US forces, fellow Iraqis, and, not least of all, one another. In Interpreters of Occupation, Campbell traces the experiences of twelve individuals from their young adulthood as members of the last Ba’thist generation, to their work as interpreters, through their navigation of the US immigration pipeline, and finally to their resettlement in the United States. Throughout, Campbell considers how these men and women grappled with issues of belonging and betrayal, both on the battlefield in Iraq and in the US-based diaspora.

During the Iraq War, thousands of young Baghdadis worked as interpreters for US troops, becoming the front line of the so-called War on Terror. Deployed by the military as linguistic as well as cultural interpreters—translating the “human terrain” of Iraq—members of this network urgently honed identification strategies amid suspicion from US forces, fellow Iraqis, and, not least of all, one another. In Interpreters of Occupation, Campbell traces the experiences of twelve individuals from their young adulthood as members of the last Ba’thist generation, to their work as interpreters, through their navigation of the US immigration pipeline, and finally to their resettlement in the United States. Throughout, Campbell considers how these men and women grappled with issues of belonging and betrayal, both on the battlefield in Iraq and in the US-based diaspora.

A nuanced and richly detailed ethnography, Interpreters of Occupation gives voice to a generation of US allies through their diverse and vividly rendered life histories. In the face of what some considered a national betrayal in Iraq and their experiences of otherness within the United States, interpreters negotiate what it means to belong to a diasporic community in flux.

2016 Prize Winner

Ellen McLarney, Soft Force: Women in Egypt’s Islamic Awakening (Princeton University Press 2015).

In the decades leading up to the Arab Spring in 2011, when Hosni Mubarak’s authoritarian regime was swept from power in Egypt, Muslim women took a leading role in developing a robust Islamist presence in the country’s public sphere. Soft Force examines the writings and activism of these women—including scholars, preachers, journalists, critics, actors, and public intellectuals—who envisioned an Islamic awakening in which women’s rights and the family, equality, and emancipation were at the center.

In the decades leading up to the Arab Spring in 2011, when Hosni Mubarak’s authoritarian regime was swept from power in Egypt, Muslim women took a leading role in developing a robust Islamist presence in the country’s public sphere. Soft Force examines the writings and activism of these women—including scholars, preachers, journalists, critics, actors, and public intellectuals—who envisioned an Islamic awakening in which women’s rights and the family, equality, and emancipation were at the center.

Challenging Western conceptions of Muslim women as being oppressed by Islam, Ellen McLarney shows how women used “soft force”—a women’s jihad characterized by nonviolent protest—to oppose secular dictatorship and articulate a public sphere that was both Islamic and democratic. McLarney draws on memoirs, political essays, sermons, newspaper articles, and other writings to explore how these women imagined the home and the family as sites of the free practice of religion in a climate where Islamists were under siege by the secular state. While they seem to reinforce women’s traditional roles in a male-dominated society, these Islamist writers also reoriented Islamist politics in domains coded as feminine, putting women at the very forefront in imagining an Islamic polity.

2016 Honorable Mention

Reina Lewis, Muslim Fashion: Contemporary Style Cultures (Duke University Press 2015).

In the shops of London’s Oxford Street, girls wear patterned scarves over their hair as they cluster around makeup counters. Alongside them, hip twenty-somethings style their head-wraps in high black topknots to match their black boot-cut trousers. Participating in the world of popular mainstream fashion—often thought to be the domain of the West—these young Muslim women are part of an emergent cross-faith transnational youth subculture of modest fashion. In treating hijab and other forms of modest clothing as fashion, Reina Lewis counters the overuse of images of veiled women as “evidence” in the prevalent suggestion that Muslims and Islam are incompatible with Western modernity. Muslim Fashion contextualizes modest wardrobe styling within Islamic and global consumer cultures, interviewing key players including designers, bloggers, shoppers, store clerks, and shop owners. Focusing on Britain, North America, and Turkey, Lewis provides insights into the ways young Muslim women use multiple fashion systems to negotiate religion, identity, and ethnicity.

In the shops of London’s Oxford Street, girls wear patterned scarves over their hair as they cluster around makeup counters. Alongside them, hip twenty-somethings style their head-wraps in high black topknots to match their black boot-cut trousers. Participating in the world of popular mainstream fashion—often thought to be the domain of the West—these young Muslim women are part of an emergent cross-faith transnational youth subculture of modest fashion. In treating hijab and other forms of modest clothing as fashion, Reina Lewis counters the overuse of images of veiled women as “evidence” in the prevalent suggestion that Muslims and Islam are incompatible with Western modernity. Muslim Fashion contextualizes modest wardrobe styling within Islamic and global consumer cultures, interviewing key players including designers, bloggers, shoppers, store clerks, and shop owners. Focusing on Britain, North America, and Turkey, Lewis provides insights into the ways young Muslim women use multiple fashion systems to negotiate religion, identity, and ethnicity.

2015 Prize Winner

Marion Homes Katz, Women in the Mosque: A History of Legal Thought and Social Practice (Columbia University Press 2014).

In recognition of her work, AMEWS Book Award Committee for books published in 2014 awards Marion Holmes Katz’s Women in the Mosque: A History of Legal Thought and Social Practice, the annual AMEWS Book Award. With its focus on Islamic legal texts as rich and vibrant historical sources, Women in the Mosque offers a complex and gendered analysis of early Islamic jurisprudence and an interpretation of an understudied aspect of early Islamic history that is both subtle and humane. Katz goes beyond compiling legal rulings on women to analyze pre-modern legal commentary on women’s roles and behaviors. She draws on a vast range of legal sources, travel narratives, biographical dictionaries, and religious polemics to get at the many ways women participated in or were prevented from participating in mosque activities. Through a close reading of the texts, she shows how jurists chose their terms and frames of reference in response to changing times and circumstances. In modern times, legal arguments on women’s presence in the mosque shifted from invocations of sexual peril to calls for new patterns in domesticity. The mosque became a site for new women’s roles, which varied greatly by social class, time, and place. The Award Committee recognizes Katz’s skillful use of Arabic language legal texts and her ability to bring to life a hitherto hidden but very important aspect of pre-modern women’s daily lives and to illuminate the origins of a movement that is today impacting the lives of increasing numbers of women.

In recognition of her work, AMEWS Book Award Committee for books published in 2014 awards Marion Holmes Katz’s Women in the Mosque: A History of Legal Thought and Social Practice, the annual AMEWS Book Award. With its focus on Islamic legal texts as rich and vibrant historical sources, Women in the Mosque offers a complex and gendered analysis of early Islamic jurisprudence and an interpretation of an understudied aspect of early Islamic history that is both subtle and humane. Katz goes beyond compiling legal rulings on women to analyze pre-modern legal commentary on women’s roles and behaviors. She draws on a vast range of legal sources, travel narratives, biographical dictionaries, and religious polemics to get at the many ways women participated in or were prevented from participating in mosque activities. Through a close reading of the texts, she shows how jurists chose their terms and frames of reference in response to changing times and circumstances. In modern times, legal arguments on women’s presence in the mosque shifted from invocations of sexual peril to calls for new patterns in domesticity. The mosque became a site for new women’s roles, which varied greatly by social class, time, and place. The Award Committee recognizes Katz’s skillful use of Arabic language legal texts and her ability to bring to life a hitherto hidden but very important aspect of pre-modern women’s daily lives and to illuminate the origins of a movement that is today impacting the lives of increasing numbers of women.

2015 Honorable Mentions

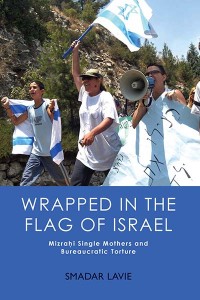

Smadar Lavie, Wrapped in the Flag of Israel: Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture (Berghahn Books 2014).

In recognition of her work, AMEWS Book Award Committee for books published in 2014 awards Smadar Lavie’s Wrapped in the Flag of Israel: Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture an Honorable Mention. Lavie offers an unflinching political analysis and cultural critique of the struggles of Mizrahi single mothers and their relationship with the domestic policies of the state of Israel and the politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Lavie, a U.S trained anthropologist who is a Mizrahi single mother herself draws on critical race and feminist theorizing to explicate the tangled web of gender, race, and class inequalities between the state of Israel’s non-European majority and European Jewish ruling minority. By focusing on the interconnection between social protest movements, state bureaucratic institutions, and political conflict, Lavie extracts the human costs of loyalty and allegiance to an ethno-religious state that inflicts “pain/torture” on its Mizrahi population, and the population’s own dependency on the perceived security provided by a state that upholds systematic discrimination. The Award Committee recognizes Lavie’s innovative approach to academic writing that combines critical theory, auto-ethnography, and memoirs to animate the lives of women in a community that has long been disenfranchised, particularly in light of limited scholarship on this topic.

In recognition of her work, AMEWS Book Award Committee for books published in 2014 awards Smadar Lavie’s Wrapped in the Flag of Israel: Mizrahi Single Mothers and Bureaucratic Torture an Honorable Mention. Lavie offers an unflinching political analysis and cultural critique of the struggles of Mizrahi single mothers and their relationship with the domestic policies of the state of Israel and the politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Lavie, a U.S trained anthropologist who is a Mizrahi single mother herself draws on critical race and feminist theorizing to explicate the tangled web of gender, race, and class inequalities between the state of Israel’s non-European majority and European Jewish ruling minority. By focusing on the interconnection between social protest movements, state bureaucratic institutions, and political conflict, Lavie extracts the human costs of loyalty and allegiance to an ethno-religious state that inflicts “pain/torture” on its Mizrahi population, and the population’s own dependency on the perceived security provided by a state that upholds systematic discrimination. The Award Committee recognizes Lavie’s innovative approach to academic writing that combines critical theory, auto-ethnography, and memoirs to animate the lives of women in a community that has long been disenfranchised, particularly in light of limited scholarship on this topic.

Amélie Le Renard, A Society of Young Women: Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi Arabia (Stanford University Press, 2014).

In recognition of her work, AMEWS Book Award Committee for books published in 2014 awards Amélie Le Renard’s A Society of Young Women: Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi Arabia an Honorable Mention. Le Renard explores young, urban Saudi women’s practices within public spaces in order to shed new light on shifting power relations, social hierarchies and gender norms in Saudi Arabia during a time of declared economic and social reform. Le Renard’s ethnographic fieldwork, conducted over a period of more than one year at the female campus of King Saud University, workplaces and shopping malls in Riyad, provides a fascinating insight into the ways in which young Saudi women renegotiate gender norms through creatively appropriating non-confrontational discourses, such as personal development and the state’s reform project, as well as through the daily repetition of transgressions of official Islamic rules. In this way, they position themselves beyond highly politicized debates about women’s rights, framed within a binary of ‘Western influence’ versus ‘authenticity’. Le Renard highlights an apparent paradox in that Riyad’s gender-segregated environment and women-only spaces, including semi-closed, securitized spaces such as shopping malls, facilitate the spread of transgressive practices, and that some young women do not experience mixed spaces as emancipatory. The Award Committee recognizes Le Renard’s sensitivity and accomplishment in dealing with a subject that generally remains understudied in the academic literature and oversimplified in popular media and considers this work to be an innovative contribution to the field Middle East women’ studies.

In recognition of her work, AMEWS Book Award Committee for books published in 2014 awards Amélie Le Renard’s A Society of Young Women: Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi Arabia an Honorable Mention. Le Renard explores young, urban Saudi women’s practices within public spaces in order to shed new light on shifting power relations, social hierarchies and gender norms in Saudi Arabia during a time of declared economic and social reform. Le Renard’s ethnographic fieldwork, conducted over a period of more than one year at the female campus of King Saud University, workplaces and shopping malls in Riyad, provides a fascinating insight into the ways in which young Saudi women renegotiate gender norms through creatively appropriating non-confrontational discourses, such as personal development and the state’s reform project, as well as through the daily repetition of transgressions of official Islamic rules. In this way, they position themselves beyond highly politicized debates about women’s rights, framed within a binary of ‘Western influence’ versus ‘authenticity’. Le Renard highlights an apparent paradox in that Riyad’s gender-segregated environment and women-only spaces, including semi-closed, securitized spaces such as shopping malls, facilitate the spread of transgressive practices, and that some young women do not experience mixed spaces as emancipatory. The Award Committee recognizes Le Renard’s sensitivity and accomplishment in dealing with a subject that generally remains understudied in the academic literature and oversimplified in popular media and considers this work to be an innovative contribution to the field Middle East women’ studies.

2014 Prize Winner

Marcia C. Inhorn, The New Arab Man: Emergent Masculinities, Technologies, and Islam in the Middle East (Princeton University Press 2012).

Middle Eastern Muslim men have been widely vilified as terrorists, religious zealots, and brutal oppressors of women. The New Arab Man challenges these stereotypes with the stories of ordinary Middle Eastern men as they struggle to overcome infertility and childlessness through assisted reproduction. Drawing on two decades of ethnographic research across the Middle East with hundreds of men from a variety of social and religious backgrounds, Marcia Inhorn shows how the new Arab man is self-consciously rethinking the patriarchal masculinity of his forefathers and unseating received wisdoms. This is especially true in childless Middle Eastern marriages where, contrary to popular belief, infertility is more common among men than women. Inhorn captures the marital, moral, and material commitments of couples undergoing assisted reproduction, revealing how new technologies are transforming their lives and religious sensibilities. She also looks at the changing manhood of husbands who undertake transnational “egg quests”– set against the backdrop of war and economic uncertainty– out of devotion to the infertile wives they love.

Middle Eastern Muslim men have been widely vilified as terrorists, religious zealots, and brutal oppressors of women. The New Arab Man challenges these stereotypes with the stories of ordinary Middle Eastern men as they struggle to overcome infertility and childlessness through assisted reproduction. Drawing on two decades of ethnographic research across the Middle East with hundreds of men from a variety of social and religious backgrounds, Marcia Inhorn shows how the new Arab man is self-consciously rethinking the patriarchal masculinity of his forefathers and unseating received wisdoms. This is especially true in childless Middle Eastern marriages where, contrary to popular belief, infertility is more common among men than women. Inhorn captures the marital, moral, and material commitments of couples undergoing assisted reproduction, revealing how new technologies are transforming their lives and religious sensibilities. She also looks at the changing manhood of husbands who undertake transnational “egg quests”– set against the backdrop of war and economic uncertainty– out of devotion to the infertile wives they love.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]